Andrea is working in the farmyard, close to the gate that opens out to pasture. Some of the big grazers are coming down the corridor to the central paddock for water. There, approaching amongst them, she becomes aware of something small and incongruous. It is the fox that has been plaguing us, beautiful and relentless little killer. It is there using the large animals as a screen to approach the field-chickens unnoticed, or so it hopes.

But it doesn’t work. Just as she’s about to shout at the interloper, a streak of wolf-large whooly fur rockets out from behind her, followed by another and yet another These are our protectors, our livestock guardian dogs. They are almost on the fox before it realizes the very real peril it is in and bolts. By now our two other farm dogs have joined the chase. The fox won’t be getting a free lunch from us, not today. Still, it is very lucky not to have been shredded.

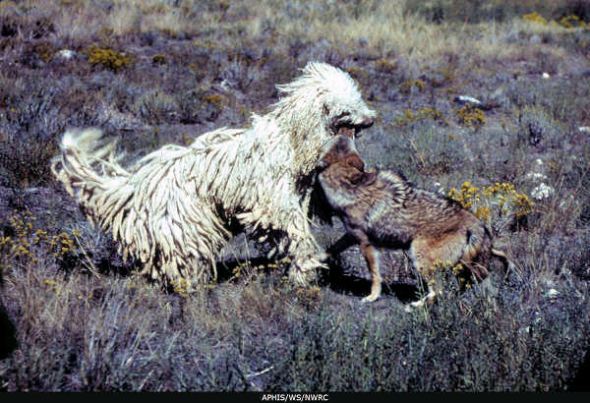

The working group “livestock guardian dogs” is composed of a number of breeds, including but not limited to: Great Pyrenees; Maremma; Akbash; Komondor; Ovcharka. The origin of these dogs is lost in antiquity, but it seems they share a common ancestor that originated perhaps in Asia. They are designed for a pastoral style of livestock husbandry, that is, one that relies on free ranging stock out on open pasture. They are raised from pups right alongside those animals they are meant to guard, and long instinct borne out of careful selection over millennia instructs them that their job is to watch over this “family” and all it contains, and to guard it with their life. (In our case, we raised our pups alongside our chickens. The yaks and the draft horses don’t need protecting.) They tend to be large dogs, capable of standing a chance against a wolf or bear if necessary. Custom sometimes suggests the dogs should receive a minimum of human contact in order for them to bond with their animal charges, but this hardly seems to be the case, Ours are extremely bonded to us yet do an exemplary job guarding, and at only slightly over a year old, they will only get better – it takes these dogs up to three years to fully mature. At any rate, we cannot imagine the loss that would be ours should we not have their friendship as we do – they are delightful creatures, full of character and personality. Furthermore, any dog this large, and programmed for savagery as the situation requires, certainly needs socialization with humans. Unless you are Ghenghis Khan, an individual infamous for harnessing his anger to produce a desired outcome. Then again, while some people who come on your place will certainly deserve to be bit on the ass by a large carnivore, Mr. Khan did not live in such a litigious age as we do today.

Amongst the breeds that compose this group of dogs are those famous for wandering large distances. I once had a friend who raised Pyrenees on his farm, for instance, this being one of the roaming breeds. When I drove over the prairie to visit him in winter, it was not uncommon to begin encountering the tracks of his dogs in the snow many miles out on the plains before I reached his farm. Two of his pups were our first livestock dogs, in fact. We couldn’t keep them on the place, nor to be honest, anywhere near it. I suppose we got them a little old to bond properly with the stock. Whatever the case, and while I personally found their free-spiritedness both fascinating and endearing, the dogs were effectively useless to us when they were five miles away and the coyote five feet from the fence. We reluctantly returned them.

Our livestock dogs that are on the place now – the brothers Sounder, Ranger and Hunter – are a trio we rescued as young pups. Their mother is a Komondor, a huge and intriguing breed that is more aggressive yet less prone to wander, their dad one of my friend’s old Pyrenees. Since spring has come on and the chickens are out ranging well afield, these new dogs have become pretty much the homebodies, tied to their job. But there was a time last winter when i was off deer hunting in the big woods that abuts our place, several miles deep into the sylvan fastness, and came upon tracks on a steep and trackless slope that i first took to be those of a pair of very large mountain lions. Wolf-sized prints. (There are lions here that leave such large tracks.) Then I detected claw-marks, which the lion of course, having retractable ones, does not leave. The prints were too round and catlike, however, to be those of wolves, found here as well. Then it suddenly dawned on me why these prints were looking so familiar as I continued to examine them. They were the tracks of my own pack! I was happy knowing they were out engaging the wilds as I was.

Our dogs are interesting to us on many levels, not the least of which includes how their physical appearance lends insights into the ancient ties between the livestock guardian breeds. For while both their parents were entirely white, two of the brothers are predominantly grey. A person might well wonder why this is so, yet in learning more about this guild of canines, will discover that other guardian breeds known from geographic regions abutting those from whence the “Komondorok” (plural for Komondor) and Pyrenees sprang indeed commonly have markings, hues and patterns not unlike those of our crosses. Breeds like the Pyrenean Mastiff, and the South Russian Ovcharka. The long buried lineages emerging readily from the ether of long ago with a little genetic coaxing.

It is normal these days when new laws are passed out in the country for them to represent some level of inhibiting nuisance to those rural folk living traditional rural lives. So it was with relief and hope that we reviewed new ordinances in our home county of Mountainview.

In Mountainview County, it is now writ in law that a barking livestock protection dog is not to be considered grounds for nuisance complaints. Nor is a livestock protection dog that is roaming off-property in the pursuit of its duties to be considered a “dog-at-large.” Rather, these dogs are now being protected as the vitally contributing rural citizens that they are, essential elements of a productive rural fabric.

Now that’s the kind of “progress” we need to see more of. Laws that actually favor, rather than hamstring, traditional farm economies.